Yuki Sakuragi

Executive/leadership Coach / ICF-ACC Coach / Mentor / Trainer

*This article is based on a lecture given by Ms. Sakuragi to Japanese people working in the pharmaceutical industry, with expressions adjusted for English-speaking readers.

I spent my childhood and adolescence in the U.S. After returning to Japan, I worked in the global R&D section of the pharmaceutical industry to bridge Japan and other countries. During that time, I felt frustrated every time I saw slight misunderstandings and struggles that occurred between non-Japanese and Japanese people. Later, as I was raising my son in Japan, I realized that the causes of such gaps were not only language itself but something else as well.

The pandemic has brought us all online and I see companies newly joining hands with Japanese partners or starting to reach out to more Japanese customers. I hope that my experiences can be of some help to more of these people who will increasingly be starting to work with people coming from a Japanese cultural background.

Japanese culture is heavily dependent on the listener’s ability

I think there is a big difference between the roles of speakers and listeners in Japan and overseas. Having been educated abroad, I believe that it is the speaker’s responsibility to make sure that the listener understands the message delivered, rather than expecting the listener to understand. In multicultural communication, putting in effort to make sure that people are being heard is REALLY important.

On the other hand, in Japan, there’s an underlying assumption that it is the role of the listener to correctly deduce and understand what is being said. I think that Japanese people are able to listen to and understand information quite well without being told each and every piece. This may be because social situations in Japan tend towards having less diversity, but I don’t think that is the only reason. When I see how children are being taught in elementary schools, where an almost one-way lecture is given by the teacher, I’m shocked to see how children patiently sit and listen (even if the explanation is very hard to understand!), and are not given much time to speak about their thoughts. I feel that the ability to listen, understand, and comprehend in Japan may have been developed in classrooms based on that style of teaching.

This listener-dependent communication style can bring upon sentiments such as, “Why aren’t you understanding what I’m saying?” or, “I didn’t understand what you said, but was too embarrassed to say so.” Or, as the listener, “It’s my fault that I didn’t understand.” In multi-cultural settings, communication cannot be listener-dependent. I would like Japanese people to be more proactive and show more behaviors such as the following: speaking in a way that can be easily understood; asking open questions to gain more information; and confirming with the speaker on what was said to make sure that both the speaker and the listener are on the same page, rather than just assuming that the listener should have understood. On the flip side, I would like people from overseas to understand this tendency of Japanese people to not do those aforementioned things, and that they generally follow a listener-dependent manner of interaction and communication.

Why do Japanese people often say “shoganai”?

What question would you ask yourself when you are unable to accomplish something you want? I think a typical question would be, “What do I need in order to achieve this goal?” This type of “What do you need for success?” question that is frequently asked in schools in the U.S. fosters a positive mindset to try to figure out what is necessary to obtain in order to achieve goals.

Japanese people, on the other hand, look back at the past and try to figure out why they couldn’t achieve their goals. In other words, it is an attitude of “learning from the past”, particularly “from past mistakes”. However, some people from overseas may think that Japanese people spend too much time looking back and reflecting on the past and trying to figure out the reasons for why things happened, but spend too little time discussing what to do next. The exhaustive amount of time spent on sharing and trying to learn from stories of the past can often make non-Japanese feel frustrated.

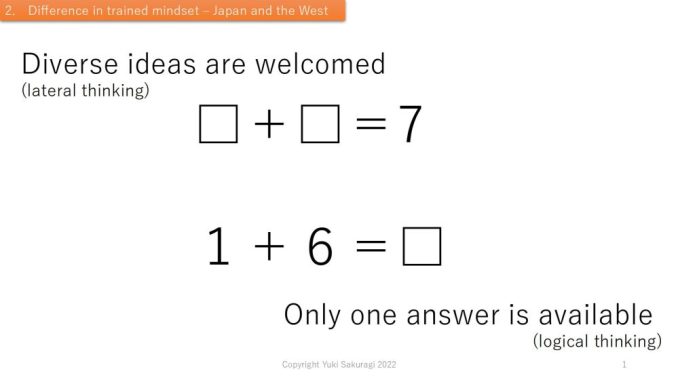

*Above slide featured in Sakuragi’s presentation.

It is often said that the above line refers to the way of thought trained in the West, and the below one is the way of thought trained in schools in Japan. In countries like the U.S., education emphasizes the importance of presenting as many ideas as possible—”lateral thinking”, divergence, or expanding thoughts.

In Japan, the emphasis is on getting to the one single correct answer, and being able to explain how one got to the correct answer—more on “logical thinking” (also known as “linear thinking”). From this way of thinking, since there is one (and only one) correct answer, everything else is considered “wrong”. Many Japanese are not comfortable with being placed in an environment where there is no right answer or where they are asked to come up with various ideas. They are simply not trained to do so.

Have you ever thought that Japan has a “shoganai (Oh well, that’s just the way it is—you can’t do anything about it)” culture? I think that this “shoganai” culture is rooted in the same as what I have stated so far. When you hit a wall, you may think, “There must be a way to get around it. Let’s try it first. If it doesn’t work out, I’ll find another way.” But in Japan, I think many people would just give up when their logical mind tells them that their chances of breaking the wall are low. When I first returned to Japan after undergoing education overseas, I was shocked to see how easily people would give up on something with only a single try or with even only the speculation that they wouldn’t achieve it. I think it’s important to recognize that there are differences in the way people are trained to think, and to accept it and formulate our approaches accordingly.

I have a lot more stories about this “shoganai” culture, which I hope I will be able to share about in future columns!

Japan, where “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down”

In Japan, there is a very famous proverb: “the nail that sticks out (or stands up), gets hammered down”. We have an atmosphere over here where being unique, or standing out from the norm in any way, is not looked upon positively by others. When I was in the U.S., words such as “unique”, and “different” were valued, and each person was considered as a unique self, or being. If I were to reword the proverb to adjust it to U.S. culture, it would be like “a nail that doesn’t stand out does not exist (no attention is paid unless you make yourself and your existence apparent)”. Having lived there I felt that I had been trained to verbalize my thoughts, to try to be heard, and to boldly show my existence.

When I returned to Japan after spending years living with this mindset, I was surprised to find out how quickly and easily people would say, “Yeah, I understand!” after so few words! It made me wonder if they even really understood what I meant. Then I realized that Japan is a society where people “assume” that you and I are based on the same norms, and that people are expected to understand each other based on the limited information provided.

In the past up until now, Japanese people generally have been listening more than talking, having been trained to use their logical/linear thinking skills rather than lateral/divergent thinking skills. They would give up when faced by barriers, saying “shoganai”, and grew up in a culture where “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down”. As the world becomes more diverse, Japan needs to adopt a different mindset—one that is more focused on taking actions for the future. At the same time, people who naturally take it for granted to approach people on their own and use all kinds of methods to communicate need to realize that Japanese people may have the opposite tendencies.

There is no such thing as good or bad culture. There are only “differences”. If we can understand each other’s point of view and collaborate by utilizing our respective strengths, I believe that we will be able to achieve unprecedented results. I hope that we can all work towards the same goals and reap wonderful fruits!

*Edited by Jennifer A. Hoff (My Eyes Tokyo)

Yuki Sakuragi

Yuki has lived in the U.S. for 8 years, beginning when she was in elementary school 4th grade. After graduating from Tokyo University of Science, she worked in global drug development for Eisai, a Japanese pharmaceutical company. When she departed from the company, after looking into different industries, she then returned to work in the pharmaceutical industry at Pfizer Japan, re-inspired by an experience of tending to illness in her family. She went on to lead a 3-year HR development initiative within Pfizer Japan’s R&D department consisting of over 500 employees, whilst orchestrating Japan’s regulatory strategy in global drug development.

Upon becoming a manager, she decided to move on to the international department of the regulatory authority that deals with review/approval of drug development (PMDA). Since departing from this authority in 2018, she has decided to operate independently.

Currently she is based in Japan where she works as an ICF-ACC certified executive/leadership coach and a mentor.

She is now enthusiastically supporting global companies in their development of people and organizations.

Yuki’s Links

Official website: naturalstep-sakuragi.com/

Facebook: facebook.com/yuki.sakuragi.career/

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/yuki-sakuragi/